For centuries, humanity has wondered if we are alone in the universe. Today, that question is moving from philosophy to science, as astronomers develop methods to detect potential life on planets orbiting distant stars. The search focuses on analyzing the chemical composition of exoplanet atmospheres for signs of biological activity – so-called biosignatures.

The Exoplanet Revolution

The discovery of over 6,000 exoplanets in the last three decades has revolutionized our understanding of planetary systems. No longer is our solar system the only known example; instead, it appears to be just one of countless others. This proliferation of worlds creates a statistical likelihood that life could exist elsewhere, but simply knowing they exist is not enough. We need ways to identify them.

Atmospheric Fingerprints

One of the most promising approaches is transmission spectroscopy. When an exoplanet passes in front of its star (a transit), some of the star’s light filters through the planet’s atmosphere. Each molecule in that atmosphere absorbs light at specific wavelengths, creating a unique “barcode” pattern. Telescopes can analyze these patterns to identify the gases present.

This method isn’t perfect; signal strength depends on a molecule’s abundance and inherent detectability. For example, while nitrogen dominates Earth’s atmosphere, its barcode is weak compared to oxygen, ozone, or water. Detecting the right molecules, in the right quantities, is crucial.

Current and Future Technologies

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already begun probing exoplanet atmospheres, detecting methane, carbon dioxide, and water in several cases. However, interpretations can vary based on data analysis choices; reliable detection requires rigorous verification.

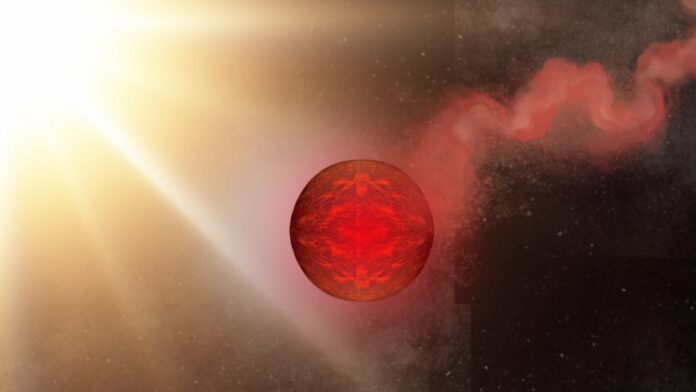

A controversial claim emerged in 2025 regarding dimethyl sulfide (DMS) on K2-18b, a sub-Neptune planet. DMS is produced by marine phytoplankton on Earth and could indicate life in K2-18b’s potential ocean world. But subsequent studies showed that alternative data analyses yielded equally plausible results, casting doubt on the original claim.

Fortunately, the future of exoplanet atmospheric analysis is bright. Several missions are planned:

- Plato (2026): Will identify Earth-like planets suitable for atmospheric spectroscopy.

- Nancy Grace Roman Telescope (2029): Will use coronagraphy to directly study planets orbiting nearby stars by blocking out their host star’s light.

- Ariel (2029): A dedicated mission designed to analyze exoplanet atmospheres in detail.

- Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO): NASA’s planned flagship mission will study 25 Earth-like planets, searching for oxygen, vegetation signatures, and even low-resolution surface maps.

What We Might Find

The Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) could potentially detect diatomic oxygen (O₂) and the “vegetation red edge” – a characteristic absorption pattern caused by photosynthetic plants. Detecting these biosignatures would be a monumental discovery, but even without conclusive proof, mapping surface features like continents and oceans would be a breakthrough.

In the coming decades, these missions will dramatically improve our ability to search for life beyond Earth. The question of whether we are alone may soon move from speculation to scientific certainty.