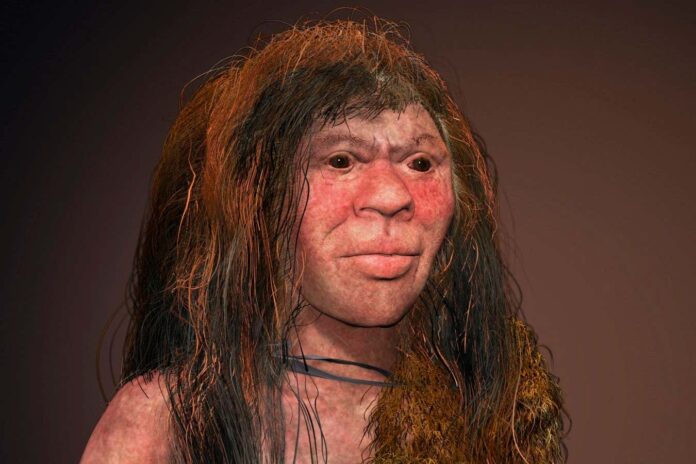

Recent advancements in DNA sequencing have provided researchers with an unprecedented glimpse into the lives of the Denisovans, an ancient group of humans who co-existed with Neanderthals and modern humans in Asia. For only the second time, scientists have successfully sequenced the full genome of a Denisovan, extracted from a 200,000-year-old tooth discovered in a Siberian cave. This groundbreaking discovery has dramatically expanded our understanding of Denisovan history, revealing a far more intricate picture than previously imagined.

Multiple Denisovan Populations and Interbreeding

The new genome data indicates that at least three distinct populations of Denisovans existed, each with its own unique history. What’s particularly striking is the evidence that early Denisovans repeatedly interbred with other ancient human groups. This includes not only interbreeding with Neanderthals – a phenomenon already established – but also with an as-yet-unidentified group of ancient humans.

“This study really expanded my understanding of the universe of the Denisovans,” says Samantha Brown, a researcher at the National Research Center on Human Evolution in Spain.

A Window into the Deep Past

The tooth from which this genome was extracted provides a glimpse into a period of human history far earlier than the previously available Denisovan genome. The estimated age of the individual – living approximately 205,000 years ago – significantly predates the previous high-quality genome, estimated to be between 55,000 and 75,000 years old. This new data shines a light on a much earlier stage of Denisovan existence, offering invaluable insights into their evolution and interactions with other ancient human groups.

Denisovan DNA in Modern Humans

Denisovans first gained prominence in 2010 when DNA from a finger bone found in Denisova cave in Siberia was found to be unlike that of either modern humans or Neanderthals. Subsequent research revealed that Denisovans interbred with modern humans: individuals in Southeast Asia, including those in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea, carry traces of Denisovan DNA. However, the source of this Denisovan DNA in modern humans remains mysterious, as it originates from a population of Denisovans that scientists know very little about.

Interbreeding with Neanderthals and a Mysterious Group

The newly sequenced genome further confirms the frequent interbreeding between Denisovans and Neanderthals, who sometimes shared territory near Denisova cave. Importantly, the genome contains evidence of a Neanderthal population that lived 7,000 to 13,000 years before the individual whose tooth was analyzed. This Neanderthal group doesn’t match any known genome, suggesting the Denisovans interbred with a previously unknown Neanderthal lineage.

Perhaps the most compelling finding is the evidence of interbreeding with a third, unidentified group of ancient humans. This group had evolved independently for hundreds of thousands of years, separate from both Denisovans and modern humans. While Homo erectus, known to be the first hominin to migrate out of Africa, is a possible candidate, it remains speculation until DNA can be recovered from this species.

“It’s endlessly fascinating that we keep discovering these new populations,” says Brown.

These discoveries highlight the complexity of ancient human evolution and the blurred lines between different groups. The new Denisovan genome is a vital piece of the puzzle, prompting further exploration and potentially revealing even more unknown branches of the human family tree.

The ongoing investigation of ancient DNA promises to continually reshape our understanding of human origins and the intricate web of interactions that have shaped our species