Researchers have uncovered a grim reality about 16th-century medicine: early practitioners weren’t afraid to experiment with bizarre ingredients, including lizard heads, human feces, and even hippopotamus teeth. The shocking discovery comes from analyzing protein residues left on the pages of two Renaissance-era medical manuals. This isn’t just historical curiosity; it reveals how desperate people were for cures, and how little they understood about hygiene or efficacy.

The Renaissance DIY Cure-Alls

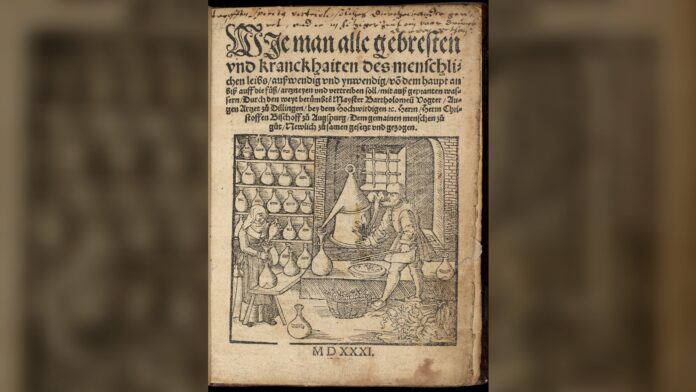

Published in 1531 by eye doctor Bartholomäus Vogtherr, “How to Cure and Expel All Afflictions and Illnesses of the Human Body” and “A Useful and Essential Little Book of Medicine for the Common Man” became instant bestsellers. These books offered remedies for everything from hair loss to bad breath, often relying on ingredients now considered repulsive or dangerous.

The books’ popularity underscores a key historical trend: the lack of regulation in early medicine. People relied on whatever they could find, leading to widespread experimentation with questionable substances.

Invisible Traces Reveal the Experimenters

A copy of Vogtherr’s manual at the University of Manchester has been yielding secrets thanks to modern proteomics analysis. Researchers extracted proteins from fingerprints and smudges left by users centuries ago. The study, published in the American Historical Review, details how these traces reveal what readers were actually doing with the recipes.

The technique is groundbreaking: researchers used plastic disks to capture proteins and mass spectrometry to identify amino-acid chains. This isn’t just about old books; it’s about a new way to understand how people interacted with knowledge in the past.

What They Were Mixing…

The analysis revealed traces of plants like European beech, watercress, and rosemary alongside hair-growth recipes. But more disturbingly, proteins from human feces were found next to instructions for treating baldness. Users weren’t just reading the book; they were applying the remedies, no matter how disgusting.

The team also identified traces of lizards, hippos, and tortoises. Pulverized lizard heads were used for hair loss, while hippopotamus teeth were believed to cure dental problems and kidney stones. These findings raise questions about the true extent of desperation and experimentation in Renaissance medicine.

Beyond the Gross-Out Factor

This research isn’t just about shocking ingredients. It shows how people sought medical help in an era before modern science. The annotated pages and dog-eared corners reveal which remedies were most frequently tried, suggesting common ailments included severe dental issues and stinking breath.

The scientists hope to expand this work, potentially even identifying individual readers based on their unique proteomic signatures. This opens up possibilities for understanding not just what people treated but who was treating them.

“Proteomics helps contextualize both the symptoms that people possibly struggled with when turning to recipe knowledge for help and the bodily effects of recipe trials and treatments,” the researchers wrote.

The study serves as a stark reminder of how far medicine has come, but also that innovation often emerges from trial and error, even when that error involves questionable ingredients.