The rapid expansion of activity in Earth orbit and beyond—driven by cheaper launches, massive satellite constellations, and a surge in commercial ventures—is exposing critical gaps in existing space law. The current legal framework, largely rooted in the 1960s, struggles to address the challenges of a dramatically more crowded and commercially active space environment.

Outdated Foundations

The primary international agreement governing space, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, was forged during the Cold War when only two nations (the U.S. and the Soviet Union) had substantial space capabilities. This treaty and subsequent agreements lack the nuance needed to manage today’s complex reality. The emergence of private actors, escalating orbital traffic, and growing interest in lunar missions demand a more dynamic approach to space governance.

Governance Challenges

The sheer number of satellites, particularly large constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink, is creating a collision risk that existing frameworks struggle to mitigate. Even when consensus exists on necessary actions—such as standardized deorbiting protocols or better space traffic management—reaching universal, binding agreements remains difficult. The fundamental problem is that the current system lacks an effective mechanism for enforcing cooperation.

A Proposed Solution: A Space COP

Harvard Kennedy School fellow Ely Sandler advocates for a “Conference of Parties” (COP) model, similar to those used in climate negotiations, to address these shortcomings. This approach would facilitate regular dialogue and incremental lawmaking, rather than relying on all-or-nothing treaties. A Space COP could focus on two key areas:

- Areas of Broad Agreement: Implementing standardized deorbiting procedures, establishing clear space traffic management protocols, and developing a liability regime to incentivize responsible behavior.

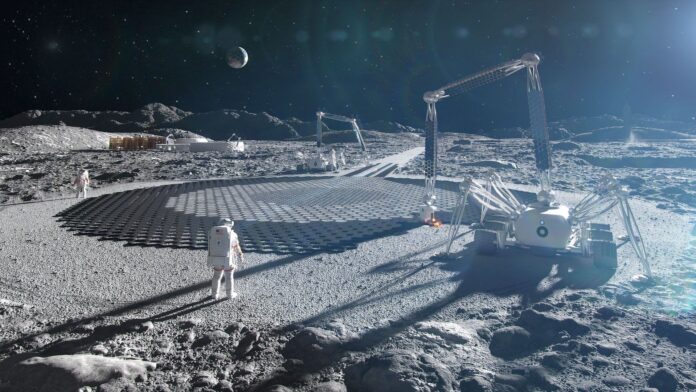

- Future Concerns: Addressing the legal ambiguities surrounding space resource mining and defining acceptable safety zones on the Moon (as proposed by the Artemis Accords).

Why This Matters

Unlike climate policy, which demands costly economic changes, many space governance measures are relatively low-cost. Simple coordination steps—such as standardized communication protocols or deorbit plans—can significantly improve safety and sustainability. The failure to adapt could lead to increased orbital debris, collisions, and disputes over resources, ultimately undermining the long-term viability of space activities.

International Cooperation Remains Possible

Despite a broader global trend away from multilateralism, space remains an area where cooperation persists. The U.S. and Russia continue to collaborate on the International Space Station, and productive debates continue within the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The need for coordinated action may outweigh geopolitical tensions in this domain.

The Path Forward

Establishing a Space COP won’t happen overnight. But shifting the conversation away from extreme options—either complete legal overhaul or no cooperation at all—is a crucial first step. The question is no longer whether space governance must evolve, but how quickly it can keep pace with the realities of the new space age.

The challenges are real, and the stakes are high. The future of space exploration and commercialization hinges on our ability to create a legal framework fit for the 21st century.