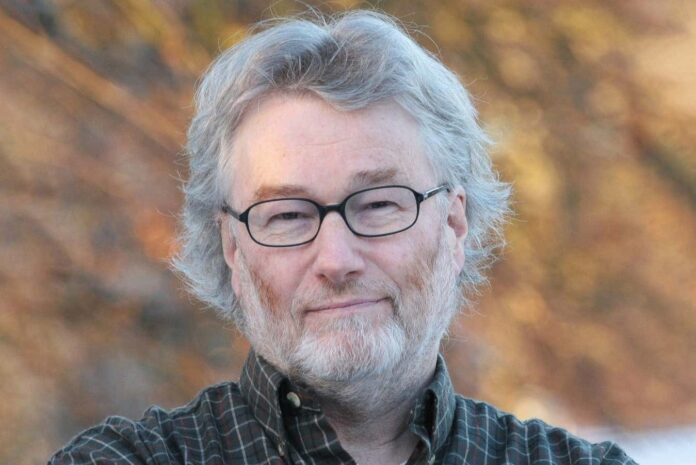

The late science fiction author Iain M. Banks, known for his Culture series, didn’t just write space operas – he constructed entire civilizations from the ground up. His world-building wasn’t merely exhaustive, but strategic. Unlike many sci-fi authors who focus on technology or conflict, Banks meticulously detailed every facet of his utopian, post-scarcity Culture, making it feel less like a fantasy and more like a plausible extrapolation of human evolution.

The Paradox of Perfection

Banks’s Culture isn’t a simple paradise. While AI “Minds” manage society benevolently, ensuring human well-being, the series explores the darker implications of such control. In novels like The Player of Games, characters grapple with boredom in a perfect world, finding solace in the chaos of less-advanced societies. This tension—between utopia and subtle imperialism—is a defining feature of Banks’s work. The Culture debates whether to intervene in less developed worlds, sometimes deciding that absorbing them, even at the cost of billions of lives, is justifiable for the greater good.

Beyond Blueprints: The Importance of Detail

Banks’s posthumously published notes and sketches, collected in The Culture: The Drawings, reveal his obsessive attention to detail. He didn’t just imagine advanced technologies; he sketched them, calculated their logistics, and even devised languages for his civilizations. These weren’t afterthoughts, but core elements of his process. The question wasn’t simply if a society could exist, but how it would function in every conceivable way.

This level of detail elevates Banks’s work beyond pure imagination. It grounds his futuristic settings in a sense of internal consistency, making them feel lived-in and accessible despite their alien nature. Writers working in the genre, including this author, often return to Banks as a guide for crafting believable worlds. The question isn’t just what a society looks like, but how its people live within it.

The Unsettling Undercurrents

Banks didn’t shy away from exploring the moral ambiguities of even his most advanced civilizations. In The State of the Art, a seemingly lighthearted story of alien visitors to Earth, he introduces moments of chilling indifference. A dinner party scene where characters casually discuss destroying Earth, even serving lab-grown human flesh, underscores the Culture’s detachment.

This jarring juxtaposition is key to Banks’s genius. It reveals that effective world-building isn’t just about geography or technology, but about tone. His blend of humor and dread creates a uniquely unsettling effect, forcing readers to confront the uncomfortable truths lurking beneath even the most idyllic surfaces.

Banks’s work serves as a masterclass in world-building: study his technical schematics, but pay closer attention to the contradictions and uneasy humor. That’s where the most profound lessons lie.

For those new to Banks’s universe, start with his sketches and notes. They offer a glimpse into his meticulous process, but also remember: the devil, and the genius, is in the details.